By Mackie M. Jalloh

The recent questioning of Thomas Dixon, Editor of the New Age Newspaper and Chairman of the Guild of Newspaper Editors, under the Cyber Security and Crime Act of 2022, has reignited debate over press freedom in Sierra Leone. Dixon was summoned by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) following a complaint from Leone Rock Metal Group, accusing him of “cyberstalking and bullying.” He was later released on bail of NLe 100,000 after several hours of interrogation.

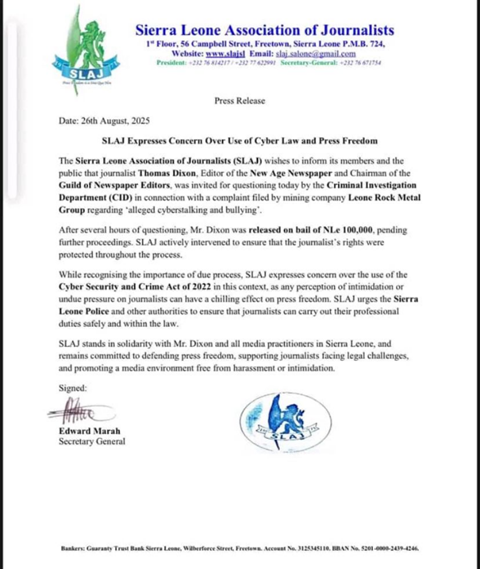

The incident, while legally procedural, has raised alarm among media practitioners and civil society observers, who argue that the law’s vague provisions risk being used to intimidate journalists and stifle investigative reporting. The Sierra Leone Association of Journalists (SLAJ) has since condemned what it terms “harassment under the guise of cybersecurity,” emphasizing the chilling effect such actions can have on democratic discourse.

The Cyber Security and Crime Act (2022) was designed to protect digital communications, combat online fraud, and deter cybercrime. While its objectives are legitimate, critics argue that the Act’s broad language allows authorities or private entities to target journalists, particularly those reporting on corporations, politicians, or state institutions.

In Dixon’s case, SLAJ points out that investigative reporting could be construed as “cyberbullying,” even when the work serves public interest. This creates a climate of uncertainty and fear within newsrooms. Editors and reporters may avoid sensitive topics to reduce the risk of legal repercussions, leading to self-censorship and a less informed public.

“Journalists should not have to weigh their professional duty against the threat of arrest or harassment,” said SLAJ Secretary-General Edward Marah. “The independence of the press is non-negotiable in a democracy.”

Thomas Dixon is not the first journalist to face pressure under the Cyber Act. Over the past two years, several reporters in Sierra Leone have reported summonses, extended interrogations, and threats linked to investigative articles exposing corruption, malpractice, or corporate negligence.

For example:

• In 2023, a radio journalist was detained for publishing an exposé on illegal land sales, only to be released without charge after public outcry.

• Another newspaper editor faced online harassment claims after reporting on misappropriation of public funds, later citing the Cyber Act as a source of intimidation.

These cases underscore a recurring theme: the law, while intended to secure digital spaces, has potentially become a tool for suppressing critical voices.

SLAJ has consistently advocated for a free and safe press. In the Dixon case, the association intervened to ensure legal procedures respected journalists’ rights, while calling on the Sierra Leone Police and other authorities to avoid using the Cyber Act as a weapon against media professionals.

Marah emphasized:

“Journalists are society’s watchdogs. When their independence is compromised, transparency, accountability, and democracy suffer.”

The association’s stance also highlights the broader societal impact of intimidation. Restricting investigative journalism limits citizens’ access to crucial information about governance, corporate practices, and human rights violations. Over time, this erodes public trust in both the media and state institutions.

Experts argue that the Cyber Act lacks clear definitions for offenses such as “cyberbullying” or “harassment.” This ambiguity allows both government and private entities to pursue journalists for actions that are part of legitimate reporting.

“The law conflates criticism with harassment,” said a senior media lawyer who requested anonymity. “Without proper safeguards, journalists are vulnerable to arbitrary summons and threats.”

SLAJ advocates for:

• Clarification of legal definitions in the Act,

• Stronger protections for journalists acting in public interest,

• Mechanisms to ensure complaints are independently verified before legal action is taken.

Sierra Leone is not alone in grappling with the balance between cybersecurity and press freedom. Across Africa and beyond, similar laws have sometimes been misused to silence dissent.

• In Uganda, the Computer Misuse Act has faced criticism for being wielded against online journalists and activists.

• Nigeria’s Cybercrimes Act has prompted self-censorship among reporters covering government corruption.

International media watchdogs, including Reporters Without Borders and the Committee to Protect Journalists, caution that poorly drafted digital laws can threaten the very freedoms they seek to protect.

SLAJ calls for urgent review and amendment of the Cyber Security and Crime Act. Clearer definitions, explicit safeguards for journalists, and transparent complaint mechanisms could prevent abuse while maintaining cybersecurity objectives.

Marah emphasized that reform is not only a matter of protecting journalists but of upholding democracy itself. He urged policymakers, corporate entities, and law enforcement agencies to respect the independence and integrity of the press, warning that failure to do so could have long-term consequences for civic trust and national development.

The Thomas Dixon case serves as a wake-up call for Sierra Leone: safeguarding digital spaces must not come at the expense of press freedom. While cybersecurity is essential, laws should not be wielded as instruments of intimidation against those holding power to account.

SLAJ’s intervention demonstrates that media solidarity, legal advocacy, and public scrutiny are crucial in defending journalists from harassment. Protecting press freedom is not just about defending individual reporters; it is about ensuring that the public retains access to vital information, democratic accountability is preserved, and society at large can thrive in transparency and trust.

The case also underscores a broader principle: in the digital age, legislation must strike a delicate balance — securing cyberspace while preserving the rights of journalists and citizens alike. Without such balance, laws meant to protect society may inadvertently weaken the democratic foundations they were designed to defend.