By Mackie M. Jalloh

Kadco is facing mounting public outrage and regulatory scrutiny following disturbing revelations surrounding the handling of large quantities of allegedly expired industrial ethanol at its Cline Town warehouse in Freetown. What initially appeared to be a routine consumer safety complaint has rapidly escalated into a full-blown public health controversy—one now raising serious questions about Kadco’s business practices, product safety, and corporate accountability.

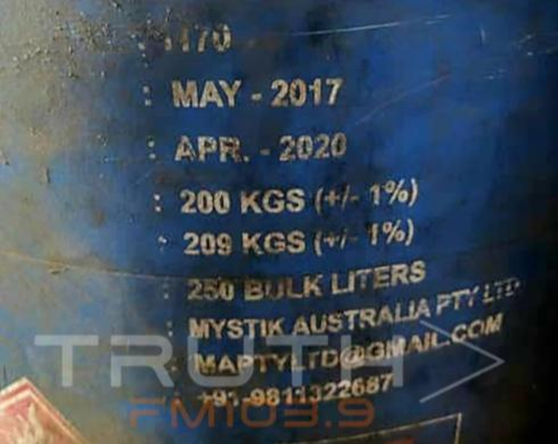

At the center of the storm is a consignment of industrial ethanol manufactured in May 2017 and officially declared expired in April 2020. According to the National Consumer Protection Agency (NCPA), more than 300 barrels of the substance were discovered during an initial inspection at Kadco’s facility. The finding immediately triggered alarm, given ethanol’s potential misuse in the production of alcoholic beverages and other consumable products.

The situation took a far more troubling turn during a follow-up inspection. Regulators returned to the warehouse only to discover that the majority of the barrels had mysteriously disappeared.

“During our first inspection, we recorded over 300 barrels,” said Edward Komeh, Deputy Executive Director of the NCPA. “When we went back, only 47 barrels were present. The company has not provided a credible explanation for the missing stock.”

For consumer protection officials, the implications are severe. The unexplained movement of such a large quantity of expired industrial ethanol raises the specter of unsafe substances being diverted into the consumer market—potentially endangering lives. Ethanol, while widely used in regulated industries, becomes a public health hazard when handled improperly, repurposed without oversight, or introduced into food and drink production outside approved standards.

Despite the gravity of the discovery, the NCPA says Kadco failed to cooperate fully with investigators. Critical documents—including import records and the Bill of Lading needed to confirm quantities, dates, and origin—were not submitted promptly. Repeated requests reportedly went unanswered, even as regulators flagged the matter as urgent.

“Without documentation, there is no transparency,” Komeh stressed. “And without transparency, public trust collapses.”

The NCPA formally escalated the issue to the National Consumer Protection Commission (NCPC), prompting the formation of a joint investigative committee involving the Sierra Leone Standards Bureau and Food and Feed Safety authorities. Yet critics argue that the regulatory response has been sluggish, allowing Kadco time and space while public safety questions remain unresolved.

Kadco itself has remained largely silent. Its public relations representative, Joseph Musa, declined to address the allegations directly, offering only that the matter is “under investigation.” That silence has done little to reassure consumers already questioning the integrity of the company’s operations and products.

The NCPC has denied any suggestion of shielding Kadco. Chief Executive Officer Lawrence Bassie confirmed that a committee was established in December 2025 and insisted that due process must be followed. Still, consumer advocates argue that when potentially hazardous substances are involved, delays can have irreversible consequences.

Laboratory experts have weighed in to clarify the technical issues. Kenneth David Kamara, Senior Laboratory Analyst at the Sierra Leone Standards Bureau, explained that while ethanol does not spoil like food, it can fall outside regulatory specifications and become unsafe for its intended use. “If a product no longer meets safety standards, it must be destroyed—not circulated,” he said.

That clarification only sharpens the central question haunting this case: if the ethanol was unfit for use, why was it not secured or destroyed, and where did the missing barrels go?

For many observers, the Kadco saga exposes deeper systemic problems—weak enforcement, delayed accountability, and a corporate culture that appears more responsive to profit than public welfare. It also serves as a stark warning to consumers. In a market where oversight is inconsistent, citizens are being urged to exercise extreme caution with Kadco products until full transparency is achieved.

“This is bigger than one company,” Komeh said. “It is about whether consumer safety truly matters.”

As laboratory tests continue and investigations drag on, the Kadco case has become a defining test of Sierra Leone’s consumer protection framework. The public is watching closely. Until every barrel is accounted for and clear answers are provided, suspicion will continue to hang over Kadco’s business operations—and trust, once broken, will not be easily restored.